We’ve All Heard the Arguments to Reauthorize the Patriot Act Before

Nick Rudnik, Valdosta Today Opinion Contributor

William Faulkner once wrote that “fiction is often the best fact.” Fiction allows the reader to set aside the biases and attitudes inherent to their own time, and consider a relevant perspective without a sense of attachment. With a growing debate over reauthorization of the Patriot Act, and the possibility of key provisions of the law expiring, perhaps there is no better fiction to consider than George Orwell’s 1949 dystopian epic, Nineteen Eighty-Four.

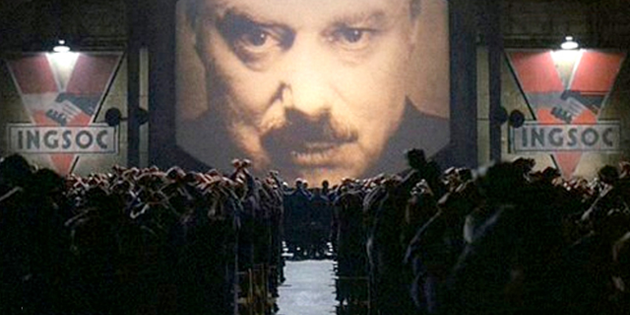

To be clear, Nineteen Eighty-Four is hyperbolical and overwrought. When Orwell penned his most celebrated work, he wrote of a deeply fictitious, conjured future. Of course, those who observe Orwell’s tome with a rigid sense of literalism will never truly understand its underpinning message: the perfectly rational and sensible nature of the police state.

In the 1949 masterpiece, we follow the life and musings of Winston Smith, a government worker at the Ministry of Truth—a state propaganda agency (and ironically named by design). Smith’s world is marked by several prevailing superpowers. He lives in Oceania, one of the superpowers, on the island of Airstrip One (or, the island of Britain, where he lives in a flat in a city that was once London). Airstrip One has been battered by incessant air raids over the preceding decades.

We follow Smith as he begins to question his fallen society—and as he fears that his doublethink, accepting to contradictory beliefs about the world, will lead to his imprisonment for thoughtcrime, or harboring unacceptable thoughts about the state.

Yes, Winston Smith is eventually arrested and “reprogrammed,” via torture, to accept and embrace the teachings of the authoritarian state. There is blatant scapegoating. There is a secret police apparatus—the Thought Police. And, there is a central leader, Big Brother, who is merely a symbol of the power and authority of the police state.

But none of these elements cut to the heart of Orwell’s work. Over a half-century removed from the writing of Orwell’s most consequential piece, what is still relevant from Nineteen Eighty-Four is the myth of a benign, autocratic surveillance state and the quality that such a myth is plausible to this day.

Think of Orwell’s invented world: a surveillance state born from great crises (a series of wars), the continuation of prolonged wars in far flung places marked by few casualties and attrition, government spin and doublespeak en masse, and a national effort to not only perpetuate, but legitimate, the surveillance state are all strikingly resonant to contemporary readers.

Think of the politics of the 2000s, the post 9/11 era, and ask: is it not the case that all of these elements are omnipresent in contemporary political discourse? Orwell still reminds us from the grave of the specious myth that is the deeply fallacious rationality of the police state. Perhaps what’s more insidious than the surveillance state itself is that it’s so readily accepted by any and all in society and the political system. There’s a crisis, a technology exists to prevent the next crisis, so government officials and citizens will accept the technology at any cost—even if that cost is our own free will, autonomy, and privacy.

The Patriot Act, specifically, and the NSA’s domestic surveillance dragnet, generally, are antithetical to life in a democratic society. Indeed, “astute” bureaucrats, “reasonable” legal scholars, and our “high-minded” elected officials insist that our domestic spying programs are legal—and therefore, the programs are right.

Perhaps, by the letter of the law, the law of the surveillance state itself, these programs are legal. Of course, they naturally would be. But that does not suppose they are democratic, nor does it presume they are right.

For we must remember that all of the spying, torture, and indoctrination inherent to Smith’s life in Oceania was also legal; and by those in “the Party” who perpetuated the system, it was both legal and right. Orwell argues the police state perpetuates its own vicious cycle by being seen as both rational, it is accepted under perfectly reasonable premises by patricians and proles alike, and right, it is legitimate and appropriate given the circumstances of the world.

By the end of Nineteen Eighty-Four, Smith is socialized, through torture and coercion, to learn to love Big Brother, the state, and its contradictory laws. The assumption by the state is that it’s far more “ethical” to execute a devoted man to Ingsoc (the ideology of Oceania), than to kill an obstinate revolutionary. When Smith dies, he truly “learns” to love the authoritarian state.

With more debate, more consideration, soon coming for the Patriot Act and its reauthorization, we’ll see just how many “rational” lawmakers adopt a similar position underscoring the necessary and sensible need for the Patriot Act, for the domestic surveillance state. And, we’ll see how many stand under the hollow cloak of secrecy and argue that our surveillance programs work, they keep us safe, and so we must continue them at any and all costs. In other words, we’ll see how many, as in the world of Winston Smith, have come to truly love Big Brother.

Nicholas A. Rudnik is currently pursuing a degree in political science with a concentration in American politics at Valdosta State University. Previously, he’s served as a congressional page in the U.S. House of Representatives during the 111th Congress and in the Office of U.S. Congressman Sanford Bishop. Further, Nick has served on staff at an institutional interest group, the Association of American Law Schools, in Washington and has worked in the private sector. He has presented his research, focused primarily on congressional parties and elections, at regional academic conferences and hopes to pursue a graduate degree in political science. Nick is currently completing two manuscripts relating to southern congressional elections and judicial decision-making in the area of campaign finance; he can be contacted via e-mail at narudnik@valdosta.edu. Follow Nick on Twitter: @NickRudnik.

Nicholas A. Rudnik is currently pursuing a degree in political science with a concentration in American politics at Valdosta State University. Previously, he’s served as a congressional page in the U.S. House of Representatives during the 111th Congress and in the Office of U.S. Congressman Sanford Bishop. Further, Nick has served on staff at an institutional interest group, the Association of American Law Schools, in Washington and has worked in the private sector. He has presented his research, focused primarily on congressional parties and elections, at regional academic conferences and hopes to pursue a graduate degree in political science. Nick is currently completing two manuscripts relating to southern congressional elections and judicial decision-making in the area of campaign finance; he can be contacted via e-mail at narudnik@valdosta.edu. Follow Nick on Twitter: @NickRudnik.